Transnational Television PhD Course - Day Three

On the third day of the PhD course the experts and students reflect on transnational television audiences and other ‘stranger things’ such as creativity. Read all about the third day in our blog.

Transnational. Television. Audiences.

The third day of the PhD course is opened by Matt Hills from Huddersfield University, addressing the topic of transnational television audiences. But from the beginning, he makes clear: “We need to interrogate all the terms in the title.”

Fan studies and audience studies overlap in a lot of ways.

Matt Hills is an expert in fan studies, who has worked on fan-communities and practices around different transnational TV phenomena, reaching from the fan-subbing of Japanese animation, over exploration of transmedia texts to cultural celebrations of Nordic Noir abroad. This range of phenomena and the differences in the depth of engagement they offer, raise the question, when the line between fans and ‘ordinary’ audiences is crossed. Matt Hills sees no clear-cut answer to this as practices flow between the groups. He argues that fan-behaviour has become more and more mainstream. Therefore: “Fan studies and audience studies overlap in a lot of ways.”

Addressing the middle term of his talk’s title - television -, Matt Hills, suggests that we as researchers are dealing with a "moving target". To illustrate this point, he shows that books on television with the words “transition” in the title have been published for decades. But the way we frame these movements is crucial. Matt Hills also mentions talk about the “death” and the crisis of television, but argues that this disregards the longer historical processes of transition. “It is important not to just jump on that bandwagon and think about continuities.”

Regarding the term “transnational”, Matt Hills points the participants to the differentiation between formal and informal transnational flows, i.e. the traditional distribution of TV abroad through the sale of rights in contrast to the “grey market” of piracy which makes media objects flow across national borders illicitly. “User-led” transnationalism, he argues, is on the rise and researchers need to find a way of including that. However, he cautions us to think of this in binary terms as both economies interact, e.g. when the industry is seeking to police piracy or when they are trying to use fan culture for promoting their product.

Following from these initial differentiations, Matt Hills zooms in on the audiences. Here, he highlights the differences between groups of fans: highly engaged fans, casual fans or even “anti-fandom”. “Different sections of the audiences”, he emphasizes, “have different emotional relationships to the show and they are aware of each other.” Furthermore, he problematizes that fan-studies tends to focus on communities around particular texts, but the broader tendencies of fandom on different levels should also be explored across different texts.

You are part of a transnational audience, if you consume a text that is marked as not being from your place of home.

Adding the issue of transnationalism to the audience, Matt Hills argues: “You are part of a transnational audience, if you consume a text that is marked as not being from your place of home.” If consumption is the only practice, this is a weak transnational audience. From this Matt Hills differentiates a strong transnational audience, that begins talking across borders. It may be highly optimistic to frame this as a “global social”, he claims, but in his studies Matt Hills has observed such relations between different national audiences.

Another perspective of the “transnational audience” is the question how the industry frames it. An example of that is Netflix, which claims that the future is all about fandom. Yet, Matt Hills cautions us not to simply accept this claim: “We need to be highly critical of Netflix’s public announcements.” The example he uses to illustrate this are Netflix’ claims about using “big data” in commissioning its originals, which presents the company as the disruptor of industry practice. Matt Hills argues that the same taste-values that impact commissioning processes in ‘classical’ TV are still involved in Netflix’ practice.

You still have to wait for a new series to ‘drop’ on Netflix.

A second point at which Netflix’ story of being a disruptor must be questioned is its claim that it brings the end of linear television. Matt Hills reminds us: “You still have to wait for a new series to ‘drop’ on Netflix.” So, there is still a time gap for each production that cannot be made to magically disappear. The instant gratification of 'bingeing', thus, still has an element of prolonged delayed gratification, Matt Hills argues. Also, he shows that Netflix sill schedules programmes: Black Mirror and Stranger Things, for example, came out with Halloween, with stories and aesthetics fitting the season. So, also when watching Netflix, “we need to think about temporality, everyday life and rituals”, Matt Hills sums up.

With Stranger Things we also enter the level of transnationality of content. The show is appropriating cultural references from Hollywood and from US television of a different age. This prompts Matt Hills to remind us of the importance of previous histories of transnational flows, which can be re-appropriated.

References to 70-80's movies in Stranger Things from Ulysse Thevenon on Vimeo.

The example of Stranger Things also raises the issue of audiences' response to Netflix’ 'Originals' and their use of fandom and transnationalism. Matt Hills quotes a comment by his colleague Dan Hassler-Forest, who expressed that the seemingly perfect match of the show to his tastes felt unsettling.

A second case Matt Hills presents to talk about transnational audiences is the Nordicana festival that ran in London for several years. It was organized by the film distributor ‘Arrow’ which also publishes crime drama on DVD under the label “Nordic Noir”. With this case, Matt Hills illustrates that fans cannot only be found online and that they are not only within the teenage age bracket.

Visiting the festival felt like “throw a stone and meet a fellow television lecturer”, Matt Hills observes. The audiences that attended, he describes as middle class with cultural capital. This is “an audience that might have an anxiety about being addressed as fans.” So, the festival offered them cultural programming alongside more typical fan-practices such as taking pictures with actors.

In the discussion following Matt Hill’s talk, the importance of th non-digital fans was also highlighted by Janet McCabe with the example of a show at the London Palladium directed at fans of Strictly Come Dancing. So, fan-studies research should not focus exclusively on online fans.

Pia Majbritt Jensen, who does audience research with Australian viewers of Danish drama, complicates the issue of the perceived “elite” audiences of Nordic Noir drama, by raising the question what such an “elite” would be defined by. In this discussion, the national specificities of cultural stratification and class emerge, which the case of Nordicana has made visible for the British context.

To reflect on their new insights into audience’s fan practices, the participants then go on to interview each other about transnational TV shows they have watched and enjoyed recently. This interview exercise shows that the data researchers gain from such interviews can be surprising, too. Also, the participants discuss the tensions between a fan-identity and a researcher-identity in their own experience of engaging with TV privately vs. academically.

Expert advice on publishing during and after the PhD

In the second knowledge exchange workshop, the experts share insights into the important forms of communicating research at different stages of PhD ‘life’.

Lothar Mikos advises the early-stage PhD students to identify associations that mirror their research interests. Furthermore: “It’s important for your career to be part of a national association and a global one.” Lothar Mikos explains this as a step towards a strategic career planning by building a network in the national research environment one intends to work in. International associations, such as ECREA, the European Communication Research and Education Association, offer several sub-sections that allow students to network with international experts in their specific field. Other international associations in the media field are the IMCR, the International Association for Media and Communication Research, or the ICA, the International Communications Association. These organizations also organize annual or bi-annual conferences that allow members to network. “If you go several years in a row”, Lothar Mikos explains, “you will meet the same people.” Also, these associations’ journals are good publishing opportunities, because all their members will read them.

Janet McCabe, co-founder and managing editor of the Journal Critical Studies in Television advises the PhD students to be patient and strategic about publishing their research. The cultures and regularities of publishing vary in different national contexts. Still, she gives some guidelines that apply broadly: “Journals are the ‘gold standard’”, because of their reviewing process that shows that the work has been approved by members of the research community. Also, she advises students to think very carefully where to submit based on the journal’s profile and the audience one wants to share the research with. A publishing strategy she recommends is submitting chapters that did not make it into the PhD.

The CST website is also a source for announcements about television conferences and Calls for Papers. The site’s blog is an opportunity for researchers to publish their ideas in short form.

You should think of this material as something that should be brought to the world.

Anne Marit Waade addresses the question of what to do with the PhD thesis once it is done. She encourages the students: “You should think of this material as something that should be brought to the world.” In an article-based PhD, the goal is clear: publishing the articles. Those with monograph PhDs might be asked to update their data before publication. Sometimes, a PhD thesis is not fit for book publication, but, what she calls, a “spin-off” might still be possible, which could also facilitate a move of fields. Her general advice is: “Take agency of your career!” – an advice that all experts agree with. Such agency could for example involve networking with the industry or other departments to open doors for other career paths. While careful career planning is adviced, Anne Marit Waade also reminds the students to keep an open mind: “Challenges don’t follow disciplines.”

In the discussion, Jeanette Steemers also reminds the students that “the PhD is just the beginning of the career.” Concerning publishing she shares the advice to “never publish if you are asked you to pay for it”, as there are several ‘bogus’ journals out there that approach researchers with ‘opportunities’ to publish for a fee.

Find your crowd & know your system.

Eva Novrup Redvall adds two more dimension to the strategic career planning. First: “Find your crowd.” This means the students should identify with which group of researcher they feel the most overlap and whom they would like to feed back on their work. Second: “Know your system.” That means knowing what is customary and expected in the particular (national) research contexts.

Eva Novrup Redvall: Transnational television and creativity

Addressing the fifth and last perspective on the course's topic, Eva Novrup Redvall looks at transnational television through the lens of “creativity”. Introducing, her colleague in the “What Makes Danish TV Drama Travel?” project, Anne Marit Waade acknowledges Eva Novrup Redvall’s expertise in fieldwork in the production of Danish TV dramas, which has been widely recognized: “When we are going abroad, people have read your work.”

Eva Novrup Redvall’s main research interest is screenwriting. Charting her own academic path, she also maps the development of this field of work and research. She explains that in the film industry, for several decades, screenwriting was considered a craft, not and art form. In the area of film studies, while she wrote her university dissertation, screenwriting was sidelined in favour of studying the “auteur”, i.e. in most cases the director of a movie. When she started her PhD project, an interest in authorship of television drama was only found in the US but nonexistent in the Danish context. However, with the international success of Danish TV drama came the attention and the interest in the Danish “way” of screenwriting. This also meant that at this time of perceived success, it was easier for her to access the writers’ rooms. However, she cautions those waiting for a “recipe” for successful scriptwriting. Her research has shown that the different creative people involved in the popular shows have very different approaches.

Next, Eva Novrup Redvall addresses “creativity”, a phenomenon that is difficult to define. Still, she shows that most definitions of creativity stress the importance of quality, originality and appropriateness. To study creativity in the screenwriting process, Eva Novrup Redvall has adapted the Hungarian/American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s model for understanding the contexts of creativity. In this adapted model, creativity in screenwriting emerges from the interplay of three areas: the individual, the domain and the field. The individual is, for example, influenced by the education received. In Denmark, most successful screenwriters receive their training at the National Film School of Denmark. Furthermore, a collaboration between the Film School and the Danish public service broadcaster DR has offered an entry point into the industry since 2004.

They want to see discussion about controversial topics such as prostitution or religion.

The domain contains the cultural tastes, trends or traditions that define television at a moment in time. Finally, ‘the field’ contains the contexts of different mandates (e.g. public service) and also financial constraints for the creative process. In the Danish case the field was changed by the influx of money from abroad via co-productions. Another important element of the field are DR’s production dogmas that, for example, call for “double storytelling”, i.e. combining high quality entertaining drama with societal issues: “They want to see discussion about controversial topics such as prostitution or religion.” An upcoming example of this is the drama Ride Upon the Storm, a Danish-French co-production that tells the story of a family of priests.

Eva Novrup Redvall illustrates these dynamics with Forbrydelsen/The Killing (2007-2012), the crime drama that ‘kick started’ Danish TV drama’s transnational career.

You need to watch it intensely to know what is going on.

The screenwriter, Søren Sveistrup, was trained at the National Film School, he had already worked on several acclaimed productions such as the Emmy-winning Nikolaj og Julie. At the same time – in the domain – programmes like 24 challenged the temporalities of narrating crime on television. The principle of double storytelling is reflected in the plot addressing issues such as warfare. Finally – as the screening of the opening of The Killing’s series III in the seminar room illustrates – the drama’s aesthetics demand the darkness of the cinema. Also, Eva Novrup Redvall reminds us of what the drama demands of the audience: “You need to watch it intensely to know what is going on.”

In the exercise following her lecture, the students discuss the elements of creativity – quality, novelty and appropriateness, as well as the model for mapping the contexts of the creative process with regard to their PhD projects.

The final discussion

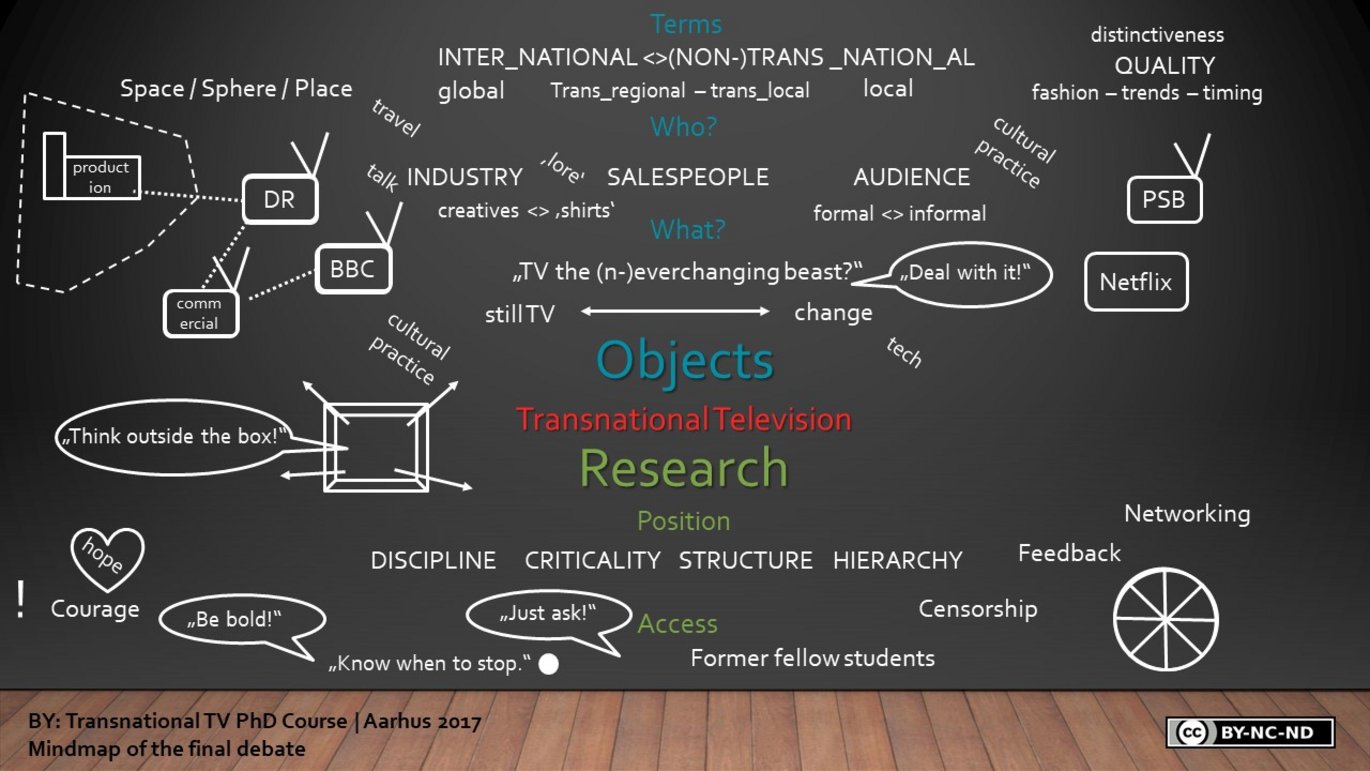

In the final debate of the PhD course the participants and experts sumarize and discuss the main points of the three days they spent thinking about the objects and the research methods of transnational television studies. Originally aiming to bring structure to the field, the resulting mind-map brings us back to the "mess" stage of creative processes...

...after all, the PhD is just the beginning!